Article

(7 mins)

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Financial risk management is not a novel concept. The notion has existed for a long time, and depending upon the industry, entities may view it as best practices, or as both a regulatory and customer-driven necessity – very seldom somewhere in between.

For many, financial risk management means hedging with derivatives. But hedging is a risk response and financial risk management is more than that. It is part and parcel to a broader enterprise risk management framework that pervades culture, people, systems, and strategy. While hedging itself may be a once or twice a year activity, financial risk management is ongoing. It requires monitoring and proactive thinking about how an entity’s risk may change in the future. It is both backward and forward-looking.

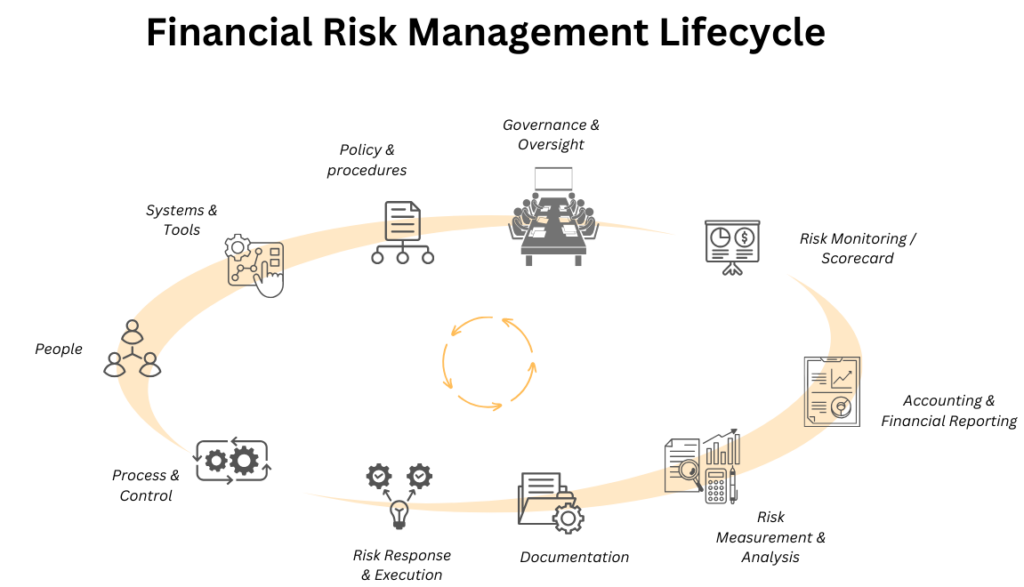

The financial risk management lifecycle depicts foundational concepts and tactical steps toward mitigating risk. It is continuous and evolves with time. The lifecycle begins at the top with governance and moves counterclockwise.

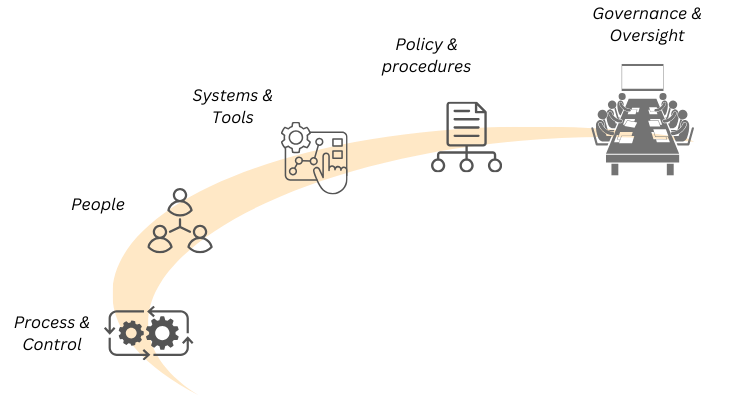

Foundation: Governance, Policy & Procedures, Systems & Tools, People, Process and Control.

Governance – Governance includes oversight from both independent and non-independent personnel, from directors of the Board to senior management, respectively. For example, a risk management committee or an Asset Liability Committee for a financial institution, or both, are considered governance functions. Financial risk is articulated, established, and revisited at this level. Directors and senior leaders must be adequately trained and informed of best practices in risk management. They must have sufficient aptitude with technical risk management concepts to be stewards for the organization and provide a high degree of constructive challenge.

Policy and procedures – Financial risk management policy and procedures are created by senior management and approved – at least annually – at the Board level. A sound policy should stand on its own and not be overtly reliant on documents, resources, or references to other sources. The policy should include the following items:

- Definition of the strategic objective(s) and how financial risk could adversely affect said objective(s). At a minimum, the risk management objective should be stated clearly.

- Risk limits and metrics – these are the “guardrails” that ensure accountability for those executing financial risk management tactics. Examples include hedge ratio minimums and maximums, value/cashflow at-Risk, position limits, etc. Sub-limits and key risk indicators should be created to signal warnings. Breaches of limits and sub-limits should result in action items for senior management ranging from revisions of financial risk positions to compensation adjustments for parties responsible for the breach.

- Governance structure includes oversight functions, periodic approval processes for changes to the policy, interdepartmental communication, reporting responsibilities and trading authorization.

- Sources of risk exposure include asset and sub-asset classification. Examples include interest rate indices, foreign currency pairs and commodities.

- Approved financial instruments to mitigate risk exposure(s) including brief descriptions of their economic purpose and how the hedging instrument satisfies the risk management objective.

- Identification of trading counterparties and dealers involved in hedge execution.

- Clear and succinct roles and responsibilities of departments involved in financial risk management, from exposure to disclosure. This may include but is not limited to governance, trading functions and authorized signatories, funding, treasury, risk management, procurement, accounting, financial reporting, and tax functions.

- Description of systems and critical tools employed for financial risk management and high-level data flow from trade execution to financial statement outcomes.

Systems and tools – Leveraging technology and assuring access to timely risk data are essential for sound risk management and strategic decision making. Ideally, there is a single system of record for financial risk management, but often this is not the case. Most entities will opt for “best of breed” platforms when managing risk. For example, risk exposures can take the shape and form of some combination of known fixed and floating rate/price contracts – alongside a forecast of estimated prices and volumes – over a pre-determined expanse of time. These known and expected contracts may live inside an Enterprise Resource Planning (“ERP”) software such as oracle or SAP. But ERP systems lack robust models for calculating metrics such as value at-Risk. Thus, a complementary Trading and Risk Management system (“xTRM”) will be necessary for financial risk management.

People – Having the right people in the “right seats” is critical. Financial risk practitioners are an extension of the risk culture of the organization. These resources must be adequately trained and possess a high degree of professional skepticism such that they will be able to identify burgeoning issues before they become material to the enterprise. Ideally, these personnel are credentialed and already have meaningful experience in some risk management capacity. It’s one thing to be both intellectual and detail-oriented, but another thing entirely to have a questioning mind and to be able to facilitate constructive challenge on a consistent basis. These resources are not easy to find and are highly compensated, especially in the financial services industry.

Process and Control – There is a saying in business that a task is “one-time,” but a process is repeatable and sustainable with little variation. And if it isn’t documented, then it’s not a process. A series of processes allows companies and their resources to achieve business objectives. Processes are a means to an end, but they introduce risk along the way. Controls mitigate risk and ensure that processes achieve their desired outcomes. A control is an activity – it is not passive. It can be preventive or detective, and automated or manual, or some combination of both. As logic would dictate, the more automated and preventive the control(s), the better they are at mitigating risk.

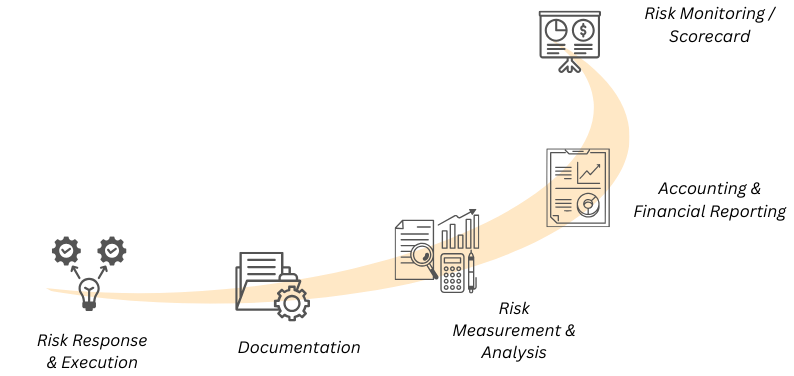

Tactical: Risk Response and Execution, Documentation, Risk Measurement and Analysis, Accounting and Financial Reporting, and Risk Monitoring / Scorecard.

Risk Response and Execution – Risk response speaks to the tactical approach to financial risk management. More specifically, this is the lifecycle phase that includes derivative execution. There is a crucial prologue to this chapter that involves quantification of the nature, timing, and extent of risk exposures. This involves in-depth analysis of the periodicity of cash inflows and outflows, and the key drivers of those amounts. Said analyses are not described here, but they have a meaningful role in defining the critical terms of the hedging instrument(s) to be executed in conformity with the financial risk management policy.

In terms of process, users must identify trading partners. For example, when executing cleared derivatives, entities would execute through a Futures Commission Merchant (“FCM”) in the case of exchange-traded derivatives or an Eligible Swap Participant (“ESP”) for cleared swaps. When executing bilateral derivatives, entities must trade with a broker/dealer or through a swap execution facility (“SEF”). Often, users choose a registered trading advisor (e.g., introducing broker, commodity trading advisor, registered investment advisor, et al.) to serve as negotiating partner when trading OTC.

Documentation – Having documentation helps solidify and memorialize processes. It’s an underappreciated, yet practical business procedure. Beyond this, financial risk management and by extension, hedge accounting guidance under Financial Accounting Standards Board ASC topic 815 requires documentation to formally designate derivatives as cash flow, fair value, or net investment hedges. This information goes above and beyond risk management policies and procedures. The following items are required for ASC 815:

- Defined hedged risk and risk management objective

- Description of the hedging instrument and hedged item

- Initial and ongoing methods for assessing hedge effectiveness

- Nature, timing, and extent of financial statement impact

Risk Measurement & Analysis – There are many ways to assess and measure risk. The risk measurement techniques must be flexible enough to accommodate not only a portfolio of risk exposures – be they currency, commodity or interest-rate driven – but also hedging instruments to ascertain the degree of cash flow or fair value offset. From a hedge accounting perspective, the following are the most common quantitative methods for hedge effectiveness assessment:

- Regression Analysis – Minimum 30 observations evaluating price/rate levels or changes in price/rate levels between hedging instrument (x) and hedged item(s)(y). Effectiveness is determined by the coefficient of determination (r2) and beta coefficient (slope, or ꞵ).

- Scenario Analysis/Stressed Dollar-Offset – Evaluation of the change from base case to stressed case scenario outcomes as a percentage of hedging instrument (x) over hedged item(s)(y). Effectiveness ratio is determined by change from base to stressed on hedging instrument (XD) divided into change from base to stressed on hedged item (YD)

- Value at-Risk (VaR) – Measures the maximum loss potential in portfolio of financial instruments over a pre-determined expanse of time with a given level of confidence. Portfolio VaR including the effect of hedging instruments (VaRx) is divided into portfolio VaR excluding the effect of hedging instruments (VaRy).

These analyses may be performed by savvy, technical accountants but are more likely carried out by middle-office treasury or risk management personnel.

Accounting and Financial Reporting – Assuming the risk measurement phase yields positive results – that is, proves a high correlation exists between hedging instrument and hedged item – the middle-office passes the baton to the back-office for accounting and financial reporting. Accountants must now reflect the debits and credits of their hedging instruments. At a high level, those entries are recorded in the following ways:

- Cash Flow hedge accounting – The change in fair value of the hedge is recorded as a Derivative Asset/Liability in the balance sheet on one side of the entry and Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (Unrealized Gain/Loss on Cash Flow Hedge) on the other side. Cash flow settlements on the hedge are timed to offset directly in earnings with the settlements from the hedged item.

- Fair Value hedge accounting – The change in fair value of the hedge is recorded as a Derivative Asset/Liability in the balance sheet on one side of the entry, and a Hedging Gain/Loss in earnings on the other side. Additionally, the change in fair value of the hedged item(s) is(are) recorded as cost basis or fair value adjustment on the balance sheet, and a Hedged Item Gain/Loss in earnings is recorded on the other side. The Hedge Gain/Loss and Hedged Item Gain/Loss effectively offset one another directly in the income statement.

- Net Investment hedge accounting – The change in fair value of the hedge is recorded as a Derivative Asset/Liability in the balance sheet on one side of the entry, and a Hedging Gain/Loss in Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (Cumulative Translation Adjustment) on the other side. The Hedging Gain/Loss is recorded as an offset to the Cumulative Translation Adjustment, or currency translation amount, from a foreign currency-denominated subsidiary, for example, or a foreign currency-denominated, majority-owned investment.

Risk Monitoring / Scorecard – Senior leaders need a mechanism to ascertain the health of its financial risk management framework. How do they know the program is doing what it is supposed to be doing? Enter the risk scorecard. Think of the risk scorecard like a score sheet for golf: the number of shots is recorded for each hole relative to a benchmark. Golfers can quickly determine whether they achieved par, bogey, or birdie, and by how much. The risk scorecard is similar in that it shows current period, and prior period, risk metric results relative to regulatory and institutional risk limits and sub-limits. Typically, these risk results would then depict some form of “check” for in-compliance, or “x” for out-of-compliance. It is intended to be a succinct and conclusive snapshot for senior leaders. It can also help refine discussion and concentration on key topics as opposed to the “kitchen sink.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, senior leaders will want to focus on out-of-compliance areas and specific metrics wherein results were dangerously close to their corresponding limits. This should prompt conversation around business objectives and whether higher-risk activities should be pared down, or if the limits need to be adjusted to accommodate strategic goals. It is this feedback loop that is essential to an optimized risk management framework.